The topic of checkpoint tuning is frequently discussed in many blogs. However, I keep coming across cases where it is kept untuned, resulting in huge wastage of server resources, struggling with poor performance and other issues.

So it’s time to reiterate the importance again with more details, especially for new users.

What is a checkpoint?

A checkpoint is a point-in-time at which PostgreSQL ensures that everything in the storage level is consistent. This is important for data recoverability. If I quote the PostgreSQL documentation

“Checkpoints are points in the sequence of transactions at which it is guaranteed that the heap and index data files have been updated with all information written before that checkpoint. Any changes made to data files before that point are guaranteed to be already on disk.”

A checkpoint needs to ensure that the database can be safely restored from the backup or in the event of a crash. A checkpoint is the point from which recovery starts by applying WALs

This is achieved by following

- Identifying “Dirty” Buffers. Because transactions leave the dirty buffers in the shared_buffer.

- Writing to the Operating System In order to avoid a massive spike in disk I/O, PostgreSQL spreads this writing process over a period of time defined by the

checkpoint_completion_targetsetting. - fsync() every file to which the writing happened, this to make sure that everything is intact and reached the storage

- Updating the Control File PostgreSQL updates a special file called

global/pg_controlwith redo location - Recycling WAL Segments

PostgreSQL will either delete these old files or rename/recycle the old WAL files (the “transaction logs”) are no longer needed for crash recovery

Yes, there is quite a bit of work.

Why is it causing uneven performance?

If we closely observe the response performance of PostgreSQL if we provide a steady workload, we may observe a saw tooth pattern

Beyond the fsync() overhead, the post-checkpoint performance dip is largely caused by Full-Page Image Writes (FPI), as explained in one of my previous blog post. These are necessary to prevent data corruption from page tearing. According to the documentation, PostgreSQL must log the entire content of a page the first time it is modified after a checkpoint. This process ensures that if a crash occurs mid-write, the page can be restored. Consequently, the high volume of FPIs right after a checkpoint creates significant I/O spikes.

Here is the extract from documentation

“… the PostgreSQL server writes the entire content of each disk page to WAL during the first modification of that page after a checkpoint. This is needed because a page write that is in process during an operating system crash might be only partially completed, leading to an on-disk page that contains a mix of old and new data …”

So immediately after the checkpoint, there will be a large number of candidate pages for this full-page write. This causes IO spike and drop in performance.

How much IO can we save if we tune ?

The truthful answer will be : Depends on the workload and schema.

However, nothing stopping us from studying the potential savings using some synthetic workload like pgbench

For this study, I created a test database to run pgbench workload with a fixed number of transactions, This will help us to compare the WAL generation for that number of transactions:

|

1 |

pgbench -c 2 -t 1110000 |

Here a fixed number of transactions (1110000) will be sent through two connections each.

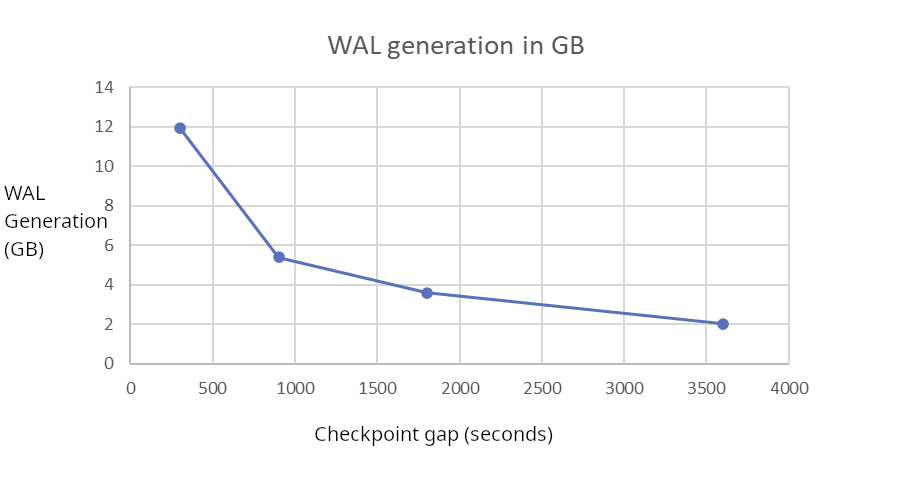

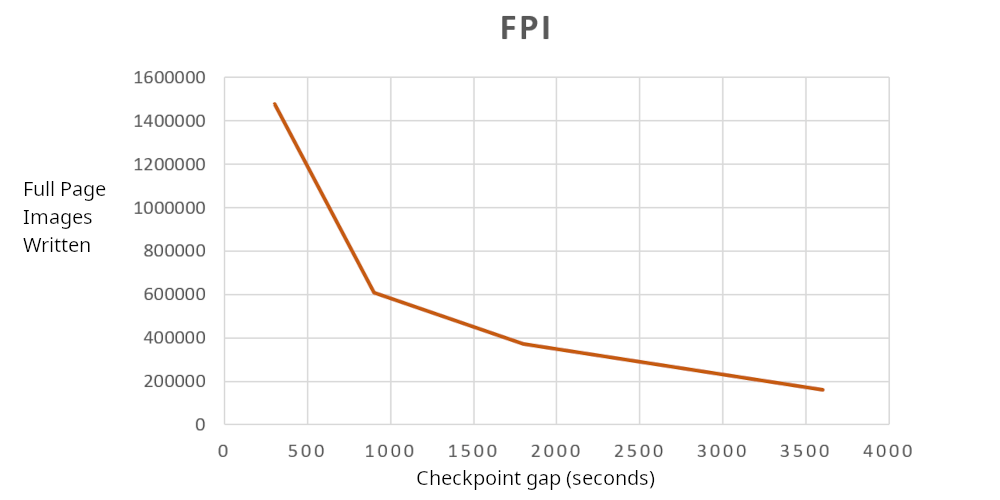

For comparison, I am taking four different duration of checkpoints, every 5 minutes (300s), 15 minutes (900s), half-an-hour (1800s) and 1 hour (3600s)

Following is my observation

| CheckPoint gap (s) | WAL GB | WAL FPI |

| 300 | 11.93793559 | 1476817 |

| 900 | 5.382575691 | 608279 |

| 1800 | 3.611122672 | 372899 |

| 3600 | 2.030713106 | 161776 |

By spreading checkpoints, WAL Generation drops from 12GB to 2GB, 6 times savings! This is very significant.

Full Page Image (FPI) writes reduced from 1.47 million to 161 thousand levels, 9 times savings. Again very significant

Yet Another factor which I want to consider is what is the percentage of Full Pages in WAL. Unfortunately, it is not easy to get that information in current PostgreSQL versions unless we use pg_waldump or pg_walinspect to extract this information.

The information available though pg_stat_wal will give us only the number of full page images (wal_fpi). But these images will get compressed before writing to WAL files.

The good news is that this feature will be available in the upcoming release : PostgreSQL 19. This feature is already committed and a new field : wal_fpi_bytes is added to pg_stat_wal view

So for the purpose of this blog, I am going to consider the uncompressed FPIs (wal_fpi * BLCKSZ). The percentage was reduced from 48.5% to 37.8% . So WAL files contain more percentage of transaction data rather than Full Page Images.

The benefits are not coming from FPI savings alone, If checkpoints are frequent, there is a high chance of the same buffer pages getting flushed again and again to files. If the checkpoints are sufficiently apart, the dirty pages can stay in shared_buffers, unless there is memory pressure.

In addition to all the resource savings, Its very common users report around 10% performance gain just by tuning the checkpoint.

Note : The above mentioned test results are on PostgreSQL 18 and data is collected from pg_stat_wal

Counter Arguments and fears

The most common concern regarding spreading checkpoints over a longer duration is the potential impact on crash recovery time. Since PostgreSQL must replay all WAL files generated since the last successful checkpoint, a longer interval between checkpoints naturally increases the volume of data that needs to be processed during recovery.

But the reality is that most of the critical systems will have standby with HA Solution like Patroni. If there is a crash, no one needs to wait for crash recovery. There will be immediate failover to standby. So the time it takes for a crash recovery doesn’t really matter for database availability. So wherever switchover to standby if the primary crashes or goes unavailable (HA), the time it takes for crash recovery becomes irrelevant.

Another factor is, even if the PostgreSQL instance is standalone without any standby to failover, there is considerably less WAL generation after the checkpoint tuning, so it becomes easy for PostgreSQL to apply those few WAL files. So a part of the problem caused by spreading the checkpoint gets solved by its own positive effects.

Yet another misconception I heard about a database without a standby to failover is : if checkpoints are 1 hour apart, recovery will take 1 hour. Definitely Not. The recovery rate is in no way related to the gap between checkpoints. Generally it takes only a few seconds or minutes to recover an hour worth of WAL. But, Yes it depends on the the amount of WAL files to be applied, Lets validate this using information from PostgreSQL logs.

Following are two examples of crash recovery of typical databases, where the infrastructure is below average.

|

1 2 3 |

LOG: database system was not properly shut down; automatic recovery in progress LOG: redo starts at 14/EB49CB90 LOG: redo done at 15/6BEECAD8 system usage: CPU: user: 18.60 s, system: 6.98 s, elapsed: 25.59 s |

Yet another

|

1 2 |

LOG: redo starts at 15/6BEECB78 LOG: redo done at 16/83686B48 system usage: CPU: user: 47.79 s, system: 14.05 s, elapsed: 69.08 s |

If we consider the first case:

The recovery is able to apply WAL from LSN 14/EB49CB90 to 15/6BEECAD8 in 25.19 seconds

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

postgres=# SELECT pg_wal_lsn_diff( '15/6BEECAD8','14/EB49CB90' )/25.19; ?column? ----------------------- 85680702.818578801112 (1 row) |

85680702 Bytes/sec = 81.71 MB/sec

On an average we often see recovery easily archiving 64MB/Sec or above, even on a slow system. This means that most of the instances will be completing the recovery in a couple of minutes even if the checkpoint is one hour apart. Well, it depends on the WALs to be applied which depends on WAL generation rate.

How to Tune Checkpointing

PostgreSQL provides mainly three parameters to tune the check-pointer behaviour

- checkpoint_timeout : This parameter allow us to plan for separating the checkpoints. Because on every checkpoint_timout, a checkpoint will be triggered. So effectively this is the maximum time between two checkpoints. If we are planning to have automatic checkpoints separated by 1 hour, this is the first parameter which we should be adjusting. I generally prefer a value of 30 minutes (1800s) minimum for production systems with Physical standbys.

- max_wal_size : This is the maximum size target for PostgreSQL to let the WAL grow between automatic checkpoints. So if a small value of this parameter can trigger frequent checkpoints. Such frequent checkpoints will further amplify the WAL generation due to FPI as mentioned earlier, causing further knock-down effect. So this value should be set such that the PostgreSQL holds sufficient WAL files between two planned checkpoints.

- checkpoint_completion_target : which is given as a fraction of the checkpoint interval (configured by using checkpoint_timeout). The I/O rate is adjusted so that the checkpoint finishes when the given fraction of checkpoint_timeout seconds have elapsed, (or before max_wal_size is exceeded, whichever is sooner). The default and generally recommended value is 0.9, Which means that the checkpointer can utilize the 90% of the time between two checkpoints to spread the I/O load. But the best recommendation I ever saw, if the checkpoint_timeouts is big enough; like half an hour or an hour is :

|

1 |

checkpoint_completion_target = (checkpoint_timeout - 2min) / checkpoint_timeout |

How to Monitor

If the parameter log_checkpoints is enabled, Details of each checkpoint will be logged into PostgreSQL log, For example, following is an log entry from a database with checkpoint_timeout of 60 minutes and checkpoint_completion_target of 0.9 (90%)

|

1 2 3 |

2026-01-14 16:16:48.181 UTC [226618] LOG: checkpoint starting: time 2026-01-14 17:10:51.463 UTC [226618] LOG: checkpoint complete: wrote 4344 buffers (1.7%), wrote 381 SLRU buffers; 0 WAL file(s) added, 0 removed, 549 recycled; write=3239.823 s, sync=0.566 s, total=3243.283 s; sync files=28, longest=0.156 s, average=0.021 s; distance=8988444 kB, estimate=11568648 kB; lsn=26/2E954A50, redo lsn=24/1514C308 |

This sample log entry tells us that a timed checkpoint (due to checkpoint_timeout ) is started at 16:16:48.181 and completed at 17:10:51.463. That means 3243282 milliseconds. This is appearing as “total” in the checkpoint completion entry. The checkpointer had to write only 4344 buffers (8kB each), which is approximately 34MB.

We can see that writing of this 34MB happened over 3239.823 s (54minutes). So the checkpointer is very gentle on I/O. This 54 minutes is because

|

1 2 |

checkpoint_timout * checkpoint_completion_arget = 60 * 0.9 = 54 |

The distance=8988444 kB tells us how much WAL is generated between checkpoints (Distance from previous checkpoint). This tells us the WAL generation rate during the time.

The estimate=11568648 kB (≈11.5 GB) represents PostgreSQL’s prediction of WAL generation between THIS checkpoint and the NEXT checkpoint. PostgreSQL controls the throttle of IO to smooth the IO load such that check pointing completes before reaching max_wal_size

In addition to this, PostgreSQL presents the cumulative statistics of WAL generation though stats view pg_stat_wal (From PostgreSQL 14 onwards). Checkpointer summary information is available though pg_stat_bgwriter (till PostgreSQL 16) and there is a dedicated pg_stat_checkpointer view available from PostgreSQL 17 onward.

Summary

Check-pointing causes lots of WAL generation, which has direct impact on overall IO subsystem in the server, which in turn affects the performance, backup and WAL retention. Tuning checkpointer has many benefits

- Saves lots in terms of expensive WAL IO which is synchronous by nature

- Associated performance benefits due to considerably less IO is implicit and obvious. The difference will be very visible in those systems where IO performance and load are the constraints.

- It helps to reduce the load of WAL archiving and savings in backup infra and storage

- Less WAL generation means less chance of the system running out of space

- Less chance of standby lags.

- Saves network bandwidth, due to less data to transmitted for both replication and backups (WAL archiving).

Overall it is one of the first steps every DBA should take as part of tuning the database. Its perfectly OK to spread the checkpoint over 1hour or more if there is HA framework like Patroni.