Unveiling the Limits: A Performance Analysis of MongoDB Sharded Clusters with plgm

In any database environment, assumptions are the enemy of stability. Understanding the point at which a system transitions from efficient to saturated is essential for maintaining uptime and ensuring a consistent and reliable user experience. Identifying these limits requires more than estimation—it demands rigorous, reproducible, and scalable load testing under realistic conditions.

To support this effort, we introduced you to plgm: Percona Load Generator for MongoDB Clusters.

PLGM is a high-performance benchmarking tool written in Go and designed to simulate realistic workloads against MongoDB clusters. Its ability to accept the same collection structures and query definitions used in the application you want to test, generate complex BSON data models, support high levels of concurrency, and provide detailed real-time telemetry makes it an ideal solution for this type of analysis

This article builds directly upon our initial blog introducing PLGM, Introducing Percona Load Generator for MongoDB Clusters: The Benchmark Tool That Simulates Your Actual Application.

As detailed in that post, PLGM was created to address the limitations of known synthetic benchmarking tools like YCSB, sysbench, pocdriver, mgodatagen and others. While those tools are excellent for measuring raw hardware throughput, they often fail to predict how a database will handle specific, complex and custom application logic. PLGM differentiates itself by focusing on realism: it uses “configuration as code” to mirror your actual document structures and query patterns, ensuring that the benchmark traffic is indistinguishable from real user activity. Please read our blog post above for more information and full comparison.

Using PLGM, we executed a structured series of workloads to identify optimal concurrency thresholds, maximum throughput capacity, and potential hardware saturation points within the cluster. The analysis includes multiple workload scenarios, including a read-only baseline and several variations of mixed and read-only workload simulations.

Ultimately, these tests reinforce an important reality: performance is not a fixed value. It is a moving target that depends entirely on workload characteristics, system architecture, and how the environment is configured and optimized.

Test Environment Architecture

The environment we used for this test consists of the following architecture (all nodes have the same hardware specifications):

- Nodes: 4 vCPUs, 8 GB RAM

- Environment: Virtual machines

- Topology: 1 Load Generator (running plgm), 2 Mongos Routers, 1 Sharded Replica Set.

- Storage: 40GB Virtual Disk

Test Workload

Percona Load Generator for MongoDB Clusters comes pre-configured with a sample database, collection, and workload, allowing you to start benchmarking your environment immediately without needing to design a workload from scratch.

This is particularly useful for quickly understanding how PLGM operates and evaluating its behavior in your environment. Of course, you have full flexibility to customize the workload to suit your specific needs, as detailed in our documentation.

The default workload used in this blog post is to showcase how PLGM works, highlighting its functionality and benefits. The default workload has the following characteristics:

- Namespace: airline.flights

- Workers: 4

- Duration: 10s

- Indexes: 4

- Sharded (if you are running against a sharded cluster)

- Query Distribution:

- Select (54%)

- Update (21%)

- Insert (5%)

- Delete (10%)

- Agg (5%)

- Approximate collection size with the above settings

- Documents: 14600

- Size: 24MB

Note on collection size and document count:

The default workload performs only 5% of its operations as inserts. To generate a larger number of documents, simply adjust the query distribution ratio, batch size and concurrency. You have full control over the number of documents and the size of the database. For example, you can set PLGM_INSERT_PERCENT=100 to perform 100% inserts and PLGM_INSERT_BATCH_SIZE to increase the number of documents per batch, this would of course increase the document count and collection size accordingly.

Environment variables set for the test workload shown below

- PLGM_PASSWORD

- PLGM_URI

- PLGM_REPLICASET_NAME

Once the above env vars have been set, all you need to do is run the application:

|

1 |

./plgm_linux config_plgm.yaml |

Sample Output:

Collection stats:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

[direct: mongos] airline> printjson(statsPick("flights")); { sharded: true, size: 28088508, count: 14591, numOrphanDocs: 0, storageSize: 15900672, totalIndexSize: 4943872, totalSize: 20844544, indexSizes: { _id_: 659456, flight_id_hashed: 921600, 'flight_id_1_equipment.plane_type_1': 1163264, seats_available_1_flight_id_1: 712704, duration_minutes_1_seats_available_1_flight_id_1: 978944, 'equipment.plane_type_1': 507904 }, avgObjSize: 1925, ns: 'airline.flights', nindexes: 6, scaleFactor: 1 } |

Sample document structure:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 |

[direct: mongos] airline> db.flights.findOne() { _id: ObjectId('695eca4be9d9322e2aae97eb'), duration_minutes: 841436202, flight_id: 1491473635, origin: 'Greensboro', gate: 'F20', seats_available: 2, passengers: [ { seat_number: '5E', passenger_id: 1, name: 'Janet Miller', ticket_number: 'TCK-15920051' }, { name: 'Keagan Reynolds', ticket_number: 'TCK-71064717', seat_number: '8A', passenger_id: 2 }, ... ommitted remaining passenger list for brevity .... ], agent_first_name: 'Earnest', agent_last_name: 'Thompson', flight_date: ISODate('2025-03-24T15:04:11.182Z'), destination: 'Chicago', flight_code: 'NM855', equipment: { plane_type: 'Boeing 777', total_seats: 43, amenities: [ 'Priority boarding', 'Extra legroom', 'Power outlets', 'WiFi', 'Hot meals' ] } } |

Benchmarks

Now that you are familiar with how to use the application, we can proceed with the benchmarks. I have run six different workloads (detailed below) and provided an overall analysis demonstrating the benefits of using Percona Load Generator for MongoDB to test your cluster.

Workload #1

We began with a read-only workload to establish the theoretical maximum throughput of the cluster. We configured plgm to execute 100% find() operations targeting a specific shard key, ensuring efficient, index-optimized queries (this was defined in our custom queries.json file, you can see the readme for further details).

|

1 2 3 4 |

for x in 4 8 16 32 48 64 80 96 128; do PLGM_PASSWORD=**** PLGM_CONCURRENCY=${x} PLGM_QUERIES_PATH=queries.json PLGM_FIND_PERCENT=100 PLGM_REPLICASET_NAME="" PLGM_URI="mongodb://dan-ps-lab-mongos00.tp.int.percona.com:27017,dan-ps-lab-mongos01.tp.int.percona.com:27017" ./plgm_linux config_plgm.yaml ; sleep 15; done |

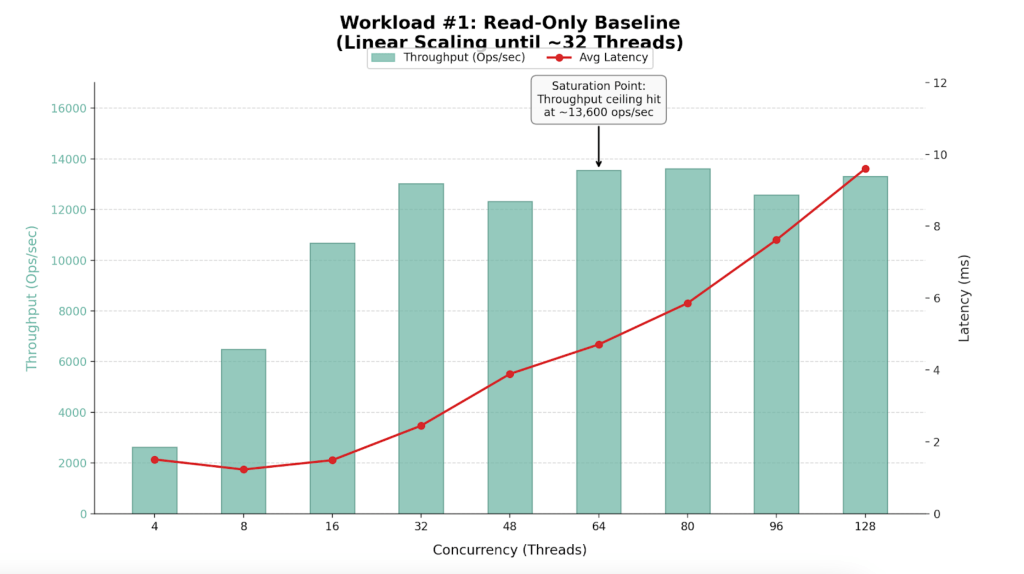

Performance Results

| Workers (Threads) | Throughput (Ops/Sec) | Avg Latency (ms) | Efficiency Verdict |

| 4 | 2,635 | 1.51 | Underutilized |

| 8 | 6,493 | 1.23 | Efficient Scaling |

| 16 | 10,678 | 1.49 | Efficient Scaling |

| 32 | 13,018 | 2.45 | Sweet Spot |

| 48 | 12,322 | 3.89 | Saturation Begins |

| 64 | 13,548 | 4.71 | Max Throughput |

| 80 | 13,610 | 5.86 | High Latency / No Gain |

| 96 | 12,573 | 7.62 | Degraded Performance |

| 128 | 13,309 | 9.60 | Oversaturated |

Findings

- The cluster performs best with 32 to 64 concurrent workers.

- The cluster hits a “performance wall” at approximately 13,600 Ops/Sec.

- Latency remains excellent (<5ms) up to 64 threads but degrades significantly (spiking to >200ms) at 96+ threads without yielding additional throughput.

- The ceiling at ~13.5k ops/sec suggests a CPU bottleneck on the single node

Analysis

- Linear Scaling (4-32 Threads): The cluster demonstrates near-perfect scalability. The hardware handles requests almost instantly.

- Saturation (48-64 Threads): Moving from 32 to 64 threads increases throughput by only ~4%, but latency doubles. The CPU is reaching capacity.

- Degradation (80+ Threads): This is classic “Resource Contention.” Requests spend more time waiting in the CPU queue than executing.

Workload #2

Following our baseline scenario, we conducted a mixed workload test (54% Reads, 46% Writes), using the same query definitions as the first workload.

|

1 2 3 |

for x in 4 8 16 32 48 64 80 96 128; do PLGM_PASSWORD=**** PLGM_CONCURRENCY=${x} PLGM_QUERIES_PATH=queries.json PLGM_REPLICASET_NAME="" PLGM_URI="mongodb://dan-ps-lab-mongos00.tp.int.percona.com:27017,dan-ps-lab-mongos01.tp.int.percona.com:27017" ./plgm_linux config_plgm.yaml ; sleep 15; done |

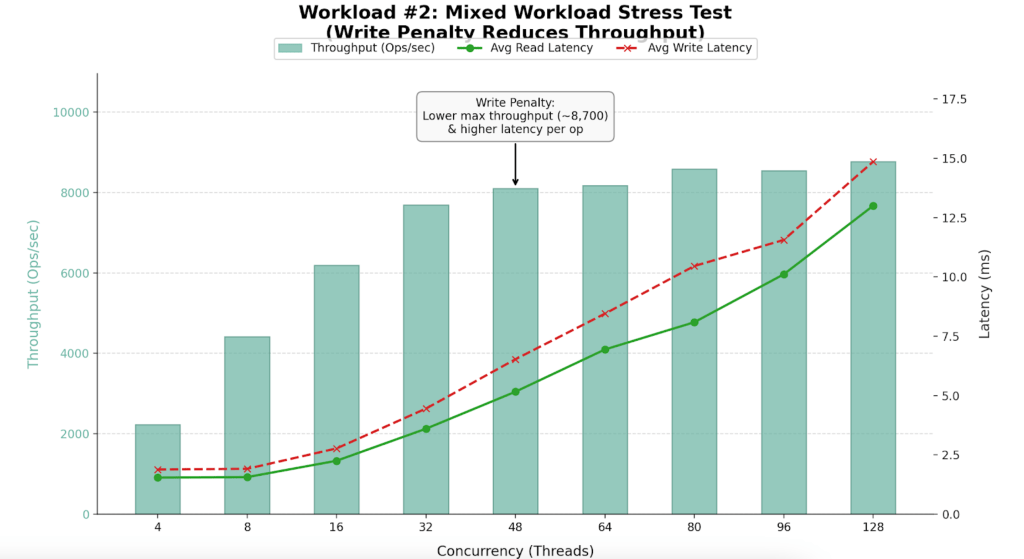

Performance Results

| Workers (Threads) | Throughput (Ops/Sec) | Avg Read Latency (ms) | Avg Write Latency (ms) | Efficiency Verdict |

| 4 | 2,225 | 1.54 | 1.88 | Underutilized |

| 16 | 6,195 | 2.25 | 2.77 | High Efficiency |

| 32 | 7,689 | 3.60 | 4.45 | Sweet Spot |

| 48 | 8,096 | 5.16 | 6.53 | Saturation Begins |

| 64 | 8,174 | 6.94 | 8.45 | Max Stability |

| 96 | 8,545 | 10.11 | 11.56 | Diminishing Returns |

| 128 | 8,767 | 13.00 | 14.86 | Oversaturated |

Findings

- Maximum sustained throughput dropped to ~8,700 Ops/Sec.

- Introducing 46% writes reduced capacity by ~35% compared to the read-only benchmark.

- Performance peaks between 32 and 64 threads.

Analysis

- Throughput drops from 13.5k to 8.7k due to the overhead of locking, Oplog replication, and journaling required for writes.

- The Saturation Point: Up to 32 threads, throughput scales linearly. Beyond 64 threads, adding workers yields almost no extra throughput but causes latency to spike to 13-15ms.

Workload #3

The third workload was executed using a different workload definition (the default), in contrast to the previous two tests that used queries.json. This workload was also a mixed workload test (54% reads and 46% writes). We conducted an analysis to identify the point at which hardware limitations began introducing scalability constraints in the system. By correlating plgm’s granular throughput data with system telemetry, we were able to pinpoint the specific resource bottleneck responsible for the performance plateau.

|

1 2 3 |

for x in 4 8 16 32 48 64 80 96 128; do PLGM_PASSWORD=**** PLGM_CONCURRENCY=${x} PLGM_REPLICASET_NAME="" PLGM_URI="mongodb://dan-ps-lab-mongos00.tp.int.percona.com:27017,dan-ps-lab-mongos01.tp.int.percona.com:27017" ./plgm_linux config_plgm.yaml ; sleep 15; done |

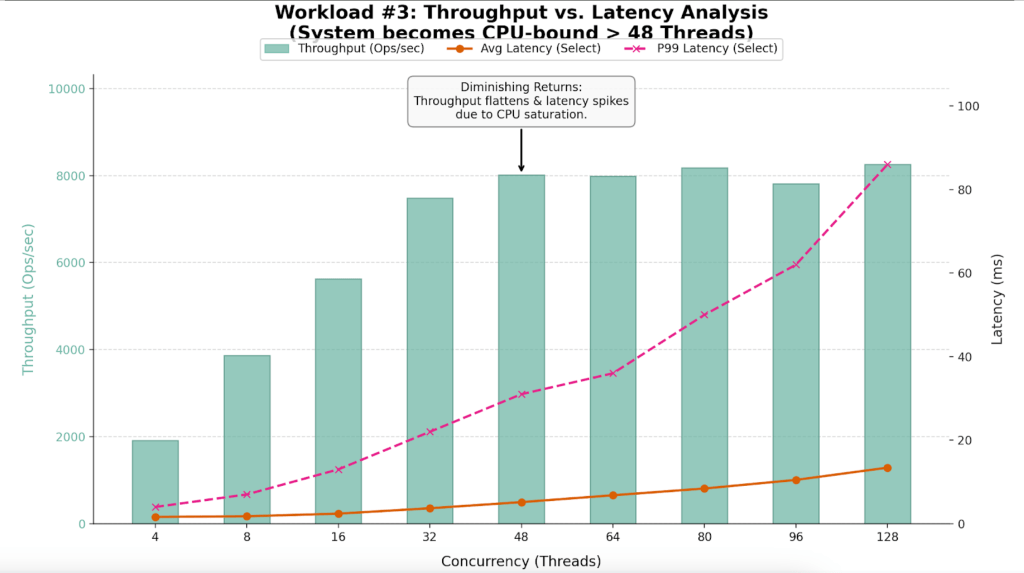

Performance Results

The table below highlights the “Diminishing Returns” phase clearly visible in this run.

| Workers (Threads) | Throughput (Ops/Sec) | Avg Latency (ms) | P99 Latency (ms) | Efficiency Verdict |

| 4 | 1,909 | 1.62 | 4.00 | Underutilized |

| 16 | 5,631 | 2.40 | 13.00 | Linear Scaling |

| 32 | 7,488 | 3.69 | 22.00 | Sweet Spot |

| 48 | 8,014 | 5.16 | 31.00 | Saturation Point |

| 64 | 7,991 | 6.80 | 36.00 | Plateau |

| 80 | 8,179 | 8.42 | 50.00 | Latency Spike |

| 96 | 7,811 | 10.48 | 62.00 | Performance Loss |

| 128 | 8,256 | 13.41 | 86.00 | Severe Queuing |

Findings

- The system saturates between 32 and 48 threads.

- At 32 threads, the system is efficient (7,488 Ops/Sec). By 48 threads, throughput gains flatten (8,014 Ops/Sec), but latency degrades by 40%.

- While average latency looks manageable, P99 (Tail) Latency triples at high load, ruining the user experience.

Analysis

- Throughput effectively flatlines around 8,000 Ops/Sec after 48 threads. The variance between 48 threads (8,014 Ops) and 128 threads (8,256 Ops) is negligible, yet the cost in latency is massive.

- The P99 column reveals the hidden cost of oversaturation. At 128 threads, 1% of users are waiting nearly 100ms for a response, compared to just 22ms at the optimal 32-thread level.

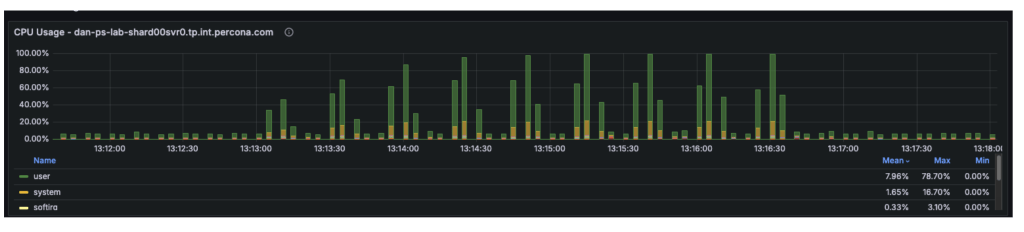

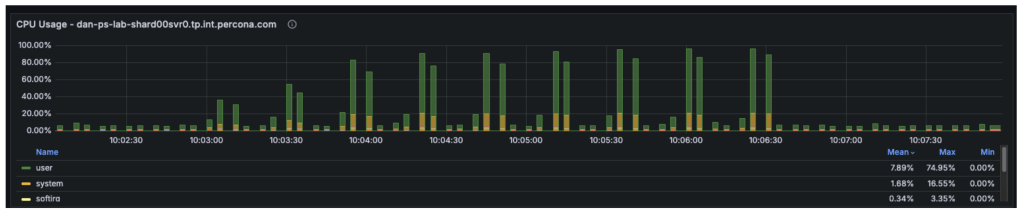

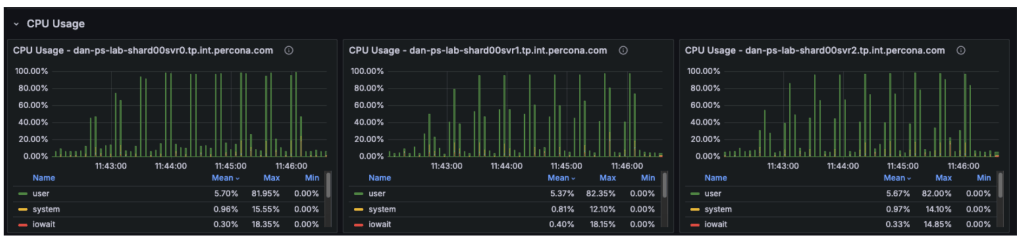

- Telemetry confirmed that at 48+ threads, the User CPU usage hit 80% and System CPU hit 16%. With the total CPU utilization at 96%, the 4 vCPUs were fully saturated, leaving requests waiting in the run queue.

Potential Improvements

Enabling secondary reads could be one of the most impactful “quick wins” for certain workload configurations. The sections below explain why this change could be beneficial, how much improvement it can provide, and the trade-offs involved.

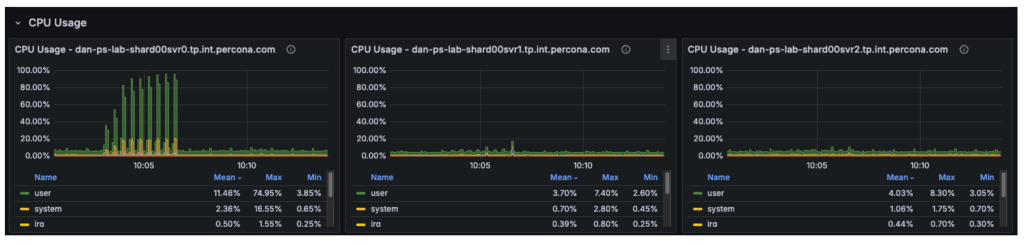

The cluster is a three-node replica set, and our observations were as follows:

- Node 1 (Primary): Running at 100% CPU, handling all writes (insert/update/delete) and all reads (select).

- Node 2 (Secondary): Largely idle, only applying replication logs.

- Node 3 (Secondary): Largely idle, only applying replication logs.

Although the cluster has 12 vCPUs in total, the workload is constrained by only 4 vCPUs on the primary. The remaining 8 vCPUs on the secondary nodes are underutilized.

Assumptions

With secondary reads enabled:

- The 54% read workload (select operations) is moved off the primary and distributed across the two secondary nodes.

- The primary is freed to focus its CPU resources almost entirely on write operations.

- Read capacity increases significantly, as two nodes are now dedicated to serving reads rather than one.

- The primary no longer processes approximately 4,700 reads per second, recovering roughly 50% of its CPU capacity for write operations.

Overall cluster throughput should increase from approximately 8,700 ops/sec to 12,000+ ops/sec, with the remaining limit determined primarily by the primary node’s write capacity.

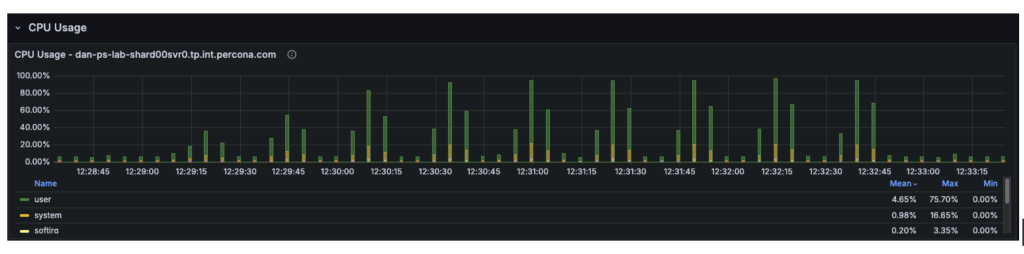

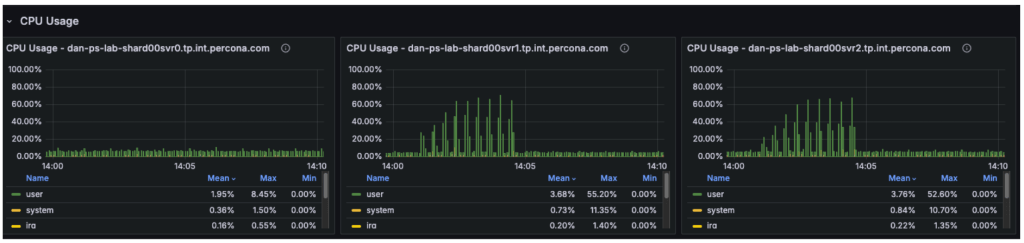

The graph below illustrates that in previous tests, the secondary nodes carried almost no workload, while the primary was fully saturated.

Trade-offs: Eventual Consistency

The “catch” is stale reads. MongoDB replication is asynchronous. There is a delay (usually milliseconds) between data being written to the Primary and appearing on the Secondary.

- Scenario: A user books a flight (Insert). The page immediately refreshes to show “My Bookings” (Select).

- Risk: If the Select hits a Secondary that hasn’t caught up yet, the new flight won’t appear for a few milliseconds.

- Mitigation: For a flight search/booking system, searching for flights (secondaryPreferred) is usually fine, but checking your own confirmed booking should usually stay on the primary (primaryPreferred)

- This approach is not recommended for such workloads where consistent reads are a requirement

Workload #4

To validate our assumptions, we can reconfigure PLGM, rather than making any changes to the infrastructure. This is one of the key advantages of using a benchmarking tool like plgm: you can modify workload behavior through configuration instead of altering the environment.

PLGM supports providing additional URI parameters either through its configuration file or via environment variables. We will use an environment variable so that no configuration files need to be modified. (For more details on available options, you can run ./plgm_linux –help or refer to the documentation)

We will run the same mixed workload as above and compare the results using the following setting:

|

1 |

PLGM_READ_PREFERENCE=secondaryPreferred |

|

1 2 3 |

for x in 4 8 16 32 48 64 80 96 128; do PLGM_PASSWORD=**** PLGM_CONCURRENCY=${x} PLGM_REPLICASET_NAME="" PLGM_READ_PREFERENCE="secondaryPreferred" PLGM_URI="mongodb://dan-ps-lab-mongos00.tp.int.percona.com:27017,dan-ps-lab-mongos01.tp.int.percona.com:27017" ./plgm_linux config_plgm.yaml ; sleep 15; done |

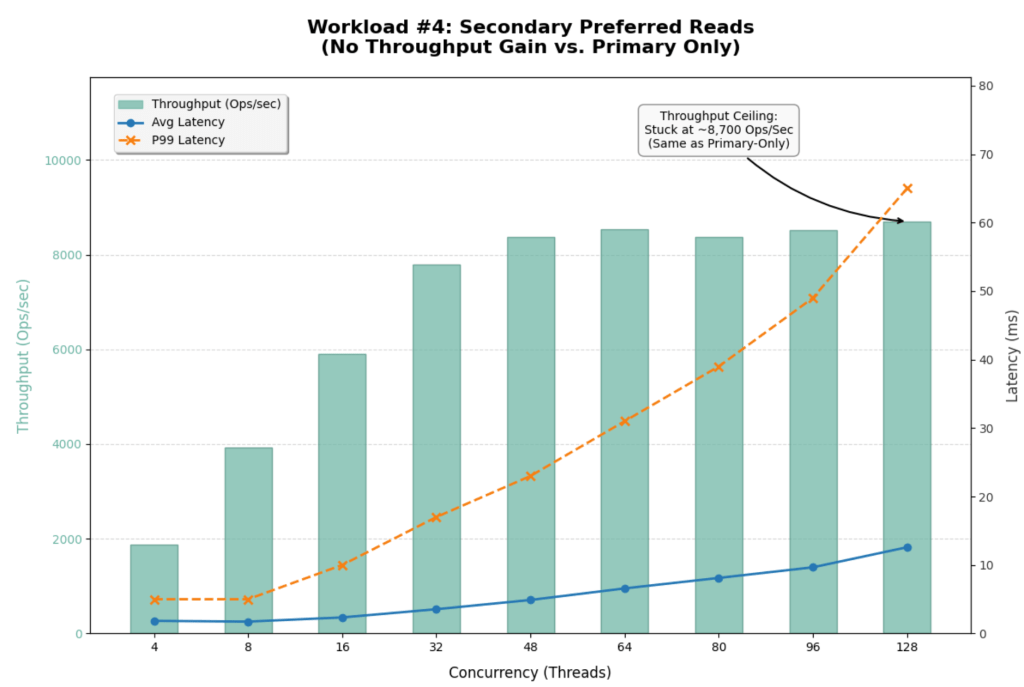

Analysis

The introduction of readPreference=secondaryPreferred yielded almost no performance improvement. In fact, it slightly degraded performance at high concurrency.

| Metric | Primary Only | Secondary Preferred | Change |

| Max Throughput | ~8,700 Ops/Sec | ~8,700 Ops/Sec | 0% (No Gain) |

| Saturation Point | ~48 Threads | ~48 Threads | Identical |

| P99 Latency (128 Threads) | 86 ms | 65 ms | ~24% Better |

| Avg Select Latency (128 Threads) | 13.41 ms | 12.59 ms | Marginal Gain |

This result strongly suggests that the Secondaries were already busy or that the bottleneck is not purely CPU on the Primary.

- Replication Lag / Oplog Contention:

- Since our workload is 46% Writes, the Secondaries are busy just applying the Oplog to keep up with the Primary.

- MongoDB replication is single-threaded (or limited concurrency) for applying writes in many versions.

- By forcing reads to the Secondaries, you are competing with the replication thread. If the Secondary falls behind, it has to work harder, and read latency suffers.

- Sharding Router Overhead (mongos):

- The bottleneck could also be the mongos routers or the network bandwidth between the mongos and the shards, rather than the shard nodes themselves.

- If mongos is CPU saturated, it doesn’t matter how many backend nodes you have; the throughput won’t increase.

- Global Lock / Latch Contention:

- At 46% writes, you might be hitting collection-level or document-level lock contention that no amount of read-replica scaling can fix.

Offloading reads to secondaries did not unlock hidden capacity for this specific write-heavy workload. The cluster is fundamentally limited by its ability to process the 46% write volume.

Workload #5

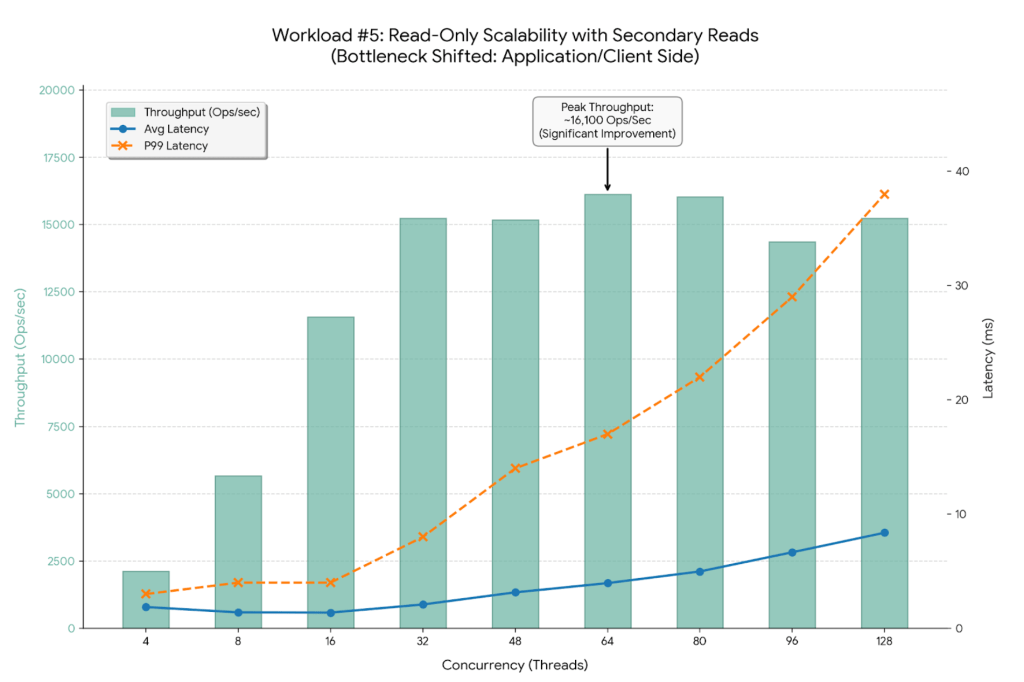

By switching to 100% Reads (PLGM_FIND_PERCENT=100) combined with Secondary Reads (PLGM_READ_PREFERENCE=secondaryPreferred), we have successfully shifted the bottleneck away from the single Primary node. The improvement is dramatic.

|

1 2 3 |

for x in 4 8 16 32 48 64 80 96 128; do PLGM_FIND_PERCENT=100 PLGM_PASSWORD=**** PLGM_CONCURRENCY=${x} PLGM_REPLICASET_NAME="" PLGM_READ_PREFERENCE="secondaryPreferred" PLGM_URI="mongodb://dan-ps-lab-mongos00.tp.int.percona.com:27017,dan-ps-lab-mongos01.tp.int.percona.com:27017" ./plgm_linux config_plgm.yaml ; sleep 15; done |

Analysis

The graph below visualizes this new “unlocked” scalability. Notice how the latency lines (Blue and Orange) stay much flatter for much longer compared to previous tests.

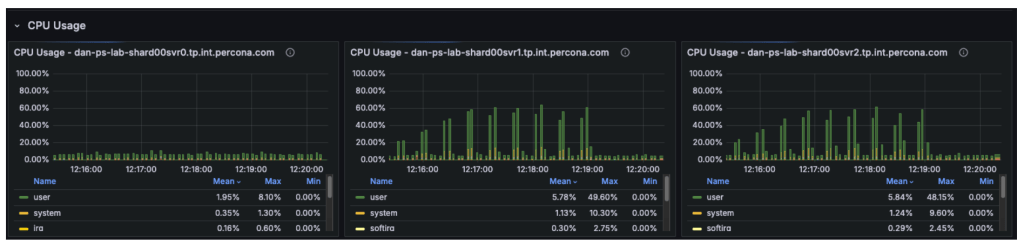

The CPU metrics and “Command Operations” charts confirm our hypothesis regarding the shift in resource utilization:

- Primary Node (svr0): CPU usage has dropped significantly. With read operations offloaded, the primary node is now essentially idle, handling only metadata updates and the replication oplog.

- Secondary Nodes (svr1, svr2): These nodes have taken over the heavy lifting, with CPU utilization rising to approximately 50-60%.

- The New Bottleneck: Since the backend secondary nodes are operating at only ~50% capacity, the database cluster itself is no longer saturated. The observed throughput plateau at ~16,000 Ops/Sec indicates the bottleneck has moved upstream. Potential candidates for this new limit include:

- Client-Side Saturation: The machine running the plgm load generator may have reached its own CPU or network limits.

- mongos Router Limits: The two router nodes might be hitting their limits for concurrent connections or packet processing.

- Network Bandwidth: The environment may be hitting the packet-per-second (PPS) ceiling of the virtual network interface.

This represents the ideal outcome of a scaling exercise: the database has been tuned so effectively that it is no longer the weak link in the application stack.

Performance Gains Summary

By optimizing the workload configuration, we achieved significant improvements across all key metrics:

- Throughput Increase:

- Previous Baseline (Primary Only): Maxed out at ~13,600 Ops/Sec.

- New Configuration (Secondary Preferred): Maxed out at ~16,132 Ops/Sec.

- Total Improvement: A ~19% increase in peak throughput.

- Latency Stability:

- Average Latency: At peak throughput (64 threads), average latency improved to 3.96ms, down from 4.71ms in the Primary-Only test.

- P99 (Tail) Latency: Stability has improved dramatically. Even at 128 threads, P99 latency is only 38ms, a massive reduction from the 320ms observed in the Primary-Only test.

Workload #6

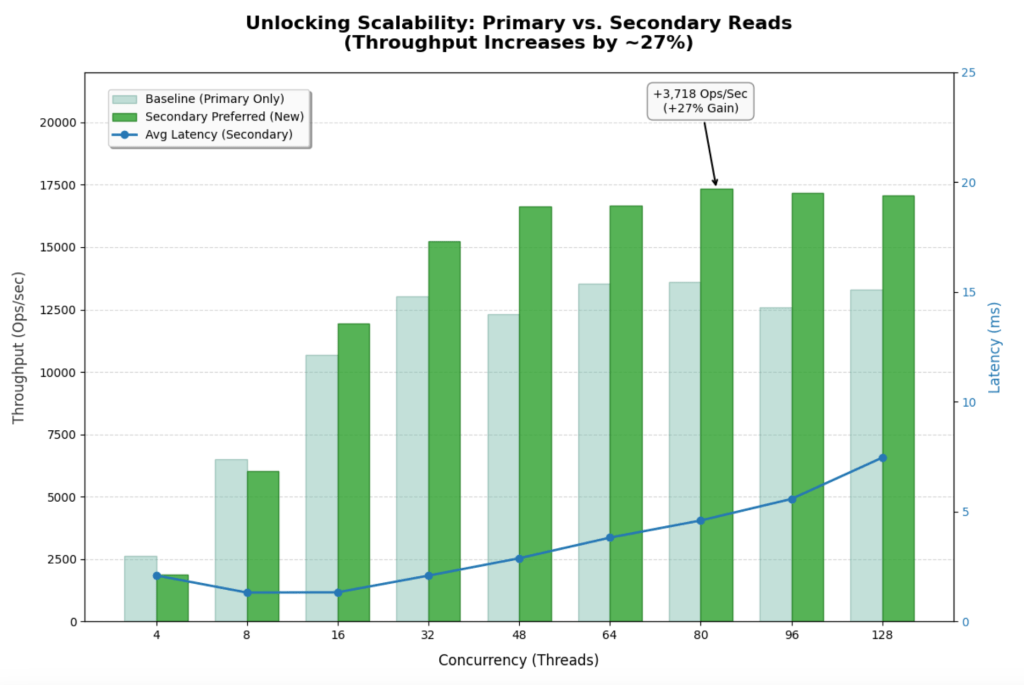

This workload represents the ideal scenario for a read-heavy application. It uses the same workload as the baseline test, with the only difference being the implementation of the secondaryPreferred option. By shifting 100% of the read traffic to the two secondary nodes, the system effectively triples its read capacity compared to the single-primary-node baseline.

|

1 2 3 4 |

for x in 4 8 16 32 48 64 80 96 128; do PLGM_READ_PREFERENCE=secondaryPreferred PLGM_PASSWORD=**** PLGM_CONCURRENCY=${x} PLGM_QUERIES_PATH=queries.json PLGM_FIND_PERCENT=100 PLGM_REPLICASET_NAME="" PLGM_URI="mongodb://dan-ps-lab-mongos00.tp.int.percona.com:27017,dan-ps-lab-mongos01.tp.int.percona.com:27017" ./plgm_linux config_plgm.yaml ; sleep 15; done |

Analysis

The graph below shows how the throughput bars continue to climb steadily all the way to 80-96 threads. The system is no longer hitting a hard “wall” at 48 threads.

- Previous Baseline (Primary Only): Maxed out at ~13,600 Ops/Sec.

- New Configuration (Secondary Preferred): Maxed out at ~17,328 Ops/Sec.

- Improvement: ~27% increase in peak throughput.

Latency Stability

- Average latency remains incredibly low (<5ms) even at very high concurrency. At 64 threads, it is 3.82ms vs 4.71ms in the baseline.

- Tail Latency (P99) is the most impressive stat. At 128 threads, P99 latency is only 32ms. In the Primary-Only test, it was 320ms. That is a 10x improvement in user experience stability under load.

Bottleneck

- The flatlining of throughput around 17k-18k ops/sec suggests you are no longer bound by database CPU. You are likely hitting limits on the client side (PLGM) or the network layer. The database nodes are happily processing everything you throw at them.

Conclusion: The Art of Precision Benchmarking

By using PLGM (Percona Load Generator for MongoDB) and telemetry, we were able to do far more than just “stress test” the database. We were able to isolate variables and incrementally step up concurrency. This precision allowed us to test different scenarios and tell a better story:

- We identified the raw CPU ceiling of a single Primary node at 13.5k Ops/Sec.

- We revealed how a realistic “Mixed Workload” (46% writes) slashes that capacity by 35%, proving that write-heavy systems cannot simply be scaled by adding more read replicas.

- By isolating a read-heavy scenario on Secondaries, we shifted the bottleneck entirely. We moved the constraint from the database hardware to the application layer, unlocking a 20%+ throughput gain and drastically stabilizing tail latency.

The Next Frontier: Application-Side Tuning

Our final test revealed an important shift in system behavior: the database is no longer the primary bottleneck. While backend nodes were operating at only ~50% utilization, overall throughput plateaued at approximately ~18k Ops/Sec, indicating the constraint has moved upstream. The performance limit now likely resides in the application server, the network layer, or the load generator itself, and future optimization efforts should focus on the following areas:

- Analyzing the application code for thread contention or inefficient connection handling.

- Query optimization

- Investigating packet limits and network bandwidth saturation

- Vertical scaling of the application servers to ensure they can drive the high-performance database cluster we have now optimized.

This is the ultimate goal of database benchmarking: to tune the data layer so effectively that it becomes invisible, forcing you to look elsewhere for the next leap in performance.